For the past few years, frustrations with education technology have been most audibly expressed through the all-too-common statement “I hate e-hallpass,” referring to the pre-acquisition name of Securly Pass. As of March 2022, its developer Eduspire Solutions told EdSurge, an edtech trade journal, that this software is being used in over 1,000 schools.

But e-hallpass is just the tip of the iceberg. All students at Gateway are more than acquainted with its shortcomings. But there are far more players in this game than one now defunct, effectively indie, software developer.

Today, large data-brokering companies like Microsoft, Apple, Google, and Amazon amass insurmountable piles of information about people—for today’s children, that amounts to 72 million data points by the time they turn thirteen. The foremost reason that companies collect data is creating profiles for advertising to you, but a malicious actor can use the data in innumerable ways.

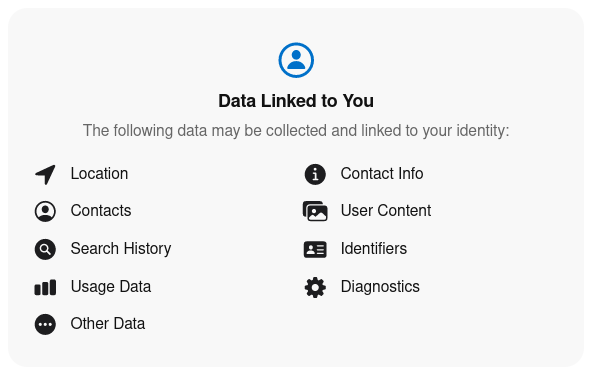

To most people, this is no surprise. Many people find this to be a creepy, occasionally convenient, fact of life. It is commonly accepted, however, that the data collected by advertisers is at least somewhat beyond that necessary for targeted advertising. I draw your attention to the now-ancient news of privacy labels in the App Store. Here’s the privacy label for Google Classroom:

Google Classroom declared that it collects information about students’ location, contacts, and search history, among other things

None of this information besides “User Content” is necessary for the operation of Classroom. (“Identifiers” refers to both the Google account used in Classroom, which is necessary, and device identifiers which are used to track you, which aren’t.)

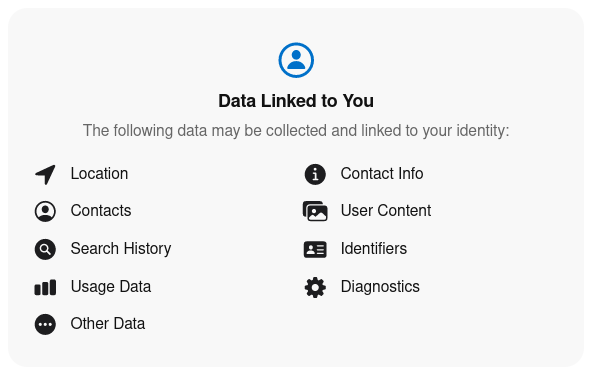

Companies also collect data from other platforms, like social media, or link it with their own services like Google does. And all of this tracking includes creepily detailed profiles. The secure (and extremely user-friendly, I might add) messaging app Signal ran an Instagram ad campaign to try to expose it, which Facebook hastily banned.

Some of the examples of Signal’s ads from their blog post

Even if we determined that all of this data collection truly was necessary for the operation of software, even in an educational setting, it’s still in the hands of a third party. Necessary data collection for the basic function of services is still bad when the data is controlled by a third party completely out of the control of the school. Companies will tell you they don’t abuse or hand out student data and that they are compliant with a host of regulations. These claims can’t be verified, however, and should not be trusted. See the false promises section.

As one person (who ironically asked to remain anonymous) has said to me, “Is it really bad that I will get ads for something I am looking to buy, and I might get good deals on it?” Apart from the “creepiness factor,” Gen Z seems fairly numb to anything related to privacy. But even if you have absolutely no regard for privacy, and you have a full-height window into your bathroom and bedroom, it remains that it’s dangerous to you personally to have all of this information in others’ control.

Once the data’s out, you are not in control of it anymore. There is no data privacy legislation in the United States, and because the legalese of a company’s privacy policy is not considered binding here, there is very little potential for recourse for unconsensual collection or distribution (“sale”) of data. The common proverb that a chain is only as strong as its weakest link applies here: if any data broker in that chain has a data breach, there is a high probability you’re impacted. Negatively. Identity theft is an exceedingly common problem.

Security vulnerabilities are inevitable in all software. When they can’t be proactively discovered or patched, however, there are actual consequences. Data breaches are commonplace among service providers of all types. Companies are often negligent and don’t fix security vulnerabilities in a timely manner. Often, partly because the source code is closed, these vulnerabilities are discovered far too late.

And with the licensing model of a lot of software, companies withhold important security updates behind a paywall of “buy the latest version.”1 For some systems, like your phone or, effectively previously, Chromebook, there are no security updates after a set amount of time: usually 1 to 3 for mobile devices and 10 years (from Google certification, not purchase, so effectively at most 8) for some Chromebooks.

I shouldn’t have to justify that data breaches are extremely common. Each week there are several / notable / data2 / breaches (and don’t forget the highly-publicized Equifax and Cambridge Analytica incidents, etc.), and the number year on year keeps increasing. Data breaches exposing even seemingly little data can contribute to identity theft. School or edtech hacks (2, 3, 4, 5, 6) are fairly common at this point.

And child identity theft / is on the rise. Credit monitoring, a common remedy offered by some businesses and schools, can’t help you once your data is leaked; it still rests on you to file police reports, compile evidence that you were not responsible for whatever activity, and clear your credit record. That is a reactive measure. It’s much easier to prevent excessive data disclosures leading to identity theft than to repair the damage following it. Thus a proactive approach is important. Even for the privacy-apathetic.

And mandatory mass collection isn’t helping that.

When you use any given service, the terms of service are a standard form contract where you have no negotiating power. The contract is thus heavily swayed towards whatever’s good for them.

One of the recurring provisions of these contracts is a class action waiver/binding arbitration provision. This means that you have no right to make or join a class action lawsuit, and you must resolve all disputes through individualized arbitration. Some will say to let people make their own contracts, but when this is forced upon you, it is unconscionable. A glaring example of that is MySchoolBucks, a popular school payment processor. I would hope this is somehow illegal because of financial regulations, but challenging the provision is a complex process, IANAL, etc.

Technology companies are also notorious for vendor lock-in; for example, the proprietary file formats underlying many applications today. Photoshop files are essentially restricted to being used in Adobe products, because the format is complex and potentially illegal to reverse-engineer. Implementors of formats like those of Microsoft Office face a 6730 page document specifying every historical bug and feature of Office products, risking incompatibility with many documents without complete compliance. Standards must be open from the beginning, and bugs must be treated as bugs. But they aren’t.

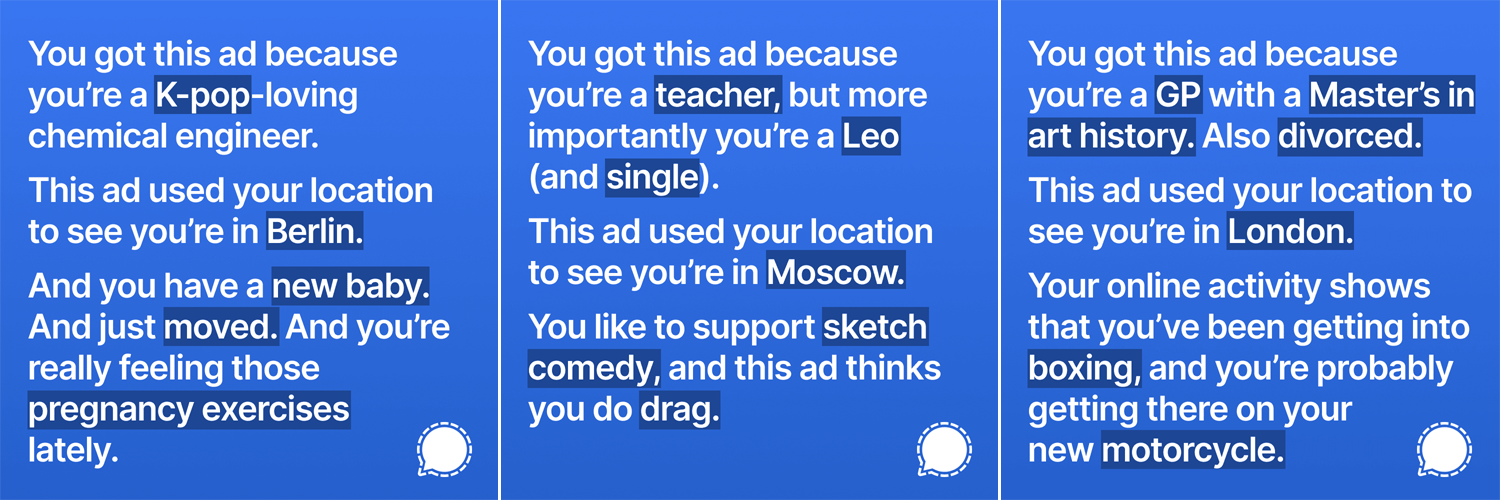

Circa today, when you log into a website or app, you’ll likely use one of these buttons:

Single sign-on buttons for Google, Clever, Facebook, and Apple

You’ll notice the only options available are fairly well-known, bar Clever, who provides single sign-on to schools specifically. Generally the options are Google, Facebook, Twitter, Apple, and/or GitHub. Noticeably fewer sites allow users to sign in without a Big Tech account. For a large number of services, alternative single sign-on providers are not usable, except in super enterprise systems.

And it’s near impossible to migrate away from Google if your SSO is tied to them. Besides SSO, Google’s practices in many areas have been monopolistic, although they may not have a monopoly. There will be another article on Google later.

When trying to sell software to a school, there are a host of regulations the school has to follow. So companies choose to put meaningless badges saying “FERPA compliant” and “COPPA compliant,” as if that somehow makes it true. It of course does not.

FERPA stands for the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, a law and set of administrative regulations stating that schools cannot disclose certain student records without consent or a valid basis. Companies don’t often follow that.

The absurdly popular PowerSchool, The Markup reported, has refused to comply with valid requests from school districts to determine what data is stored on students. From only one of 27 schools, they got a detailed list of thousands of characteristics. Which means 26 were literally unable to comply with FERPA, despite any number of fancy badges PowerSchool advertises.

Human Rights Watch, an international nonprofit whose website is blocked on the school network, shared their findings with The Washington Post that “nearly 90 percent of the educational tools were designed to send the information they collected to ad-technology companies, which could use it to estimate students’ interests and predict what they might want to buy.” Apps which are mandatory.

Self-sourced promises are useless; but popular auditing services from iKeepSafe and other companies aim to fix this. They don’t. iKeepSafe has a conflict of interest to give good ratings to its customers. Whereas a security audit is intended to help a company fix the problems and does not interfere with the sale of the program, a privacy audit is intended to obtain a certification and may interfere with the sale of the program. But what is actually suspicious is that their process is performed only “after both parties sign the NDA.” Much of the software industry prefers to keep programs closed-source; but when dealing with sensitive student data, it is dangerous to just trust closed-curtain processes like this. In recent news, the United States government, effectively chained to Microsoft products, has loudly censured them for their security practices, despite Microsoft being the literal arbiter of security for many products based on their platforms. It is also worth noting that iKeepSafe literally violates the European GDPR and American privacy laws like those of California and Colorado.3

The Student Privacy Pledge is another industry initiative to safeguard student privacy, primarily sponsored by the Future of Privacy Forum. The Future of Privacy Forum is an industry group with 210 corporate members. Many of these are Big Tech companies and law firms. This is an immediate conflict of interest. Regardless, the Electronic Frontier Foundation finds both versions of the Pledge to be riddled with issues; and because they are entirely self-regulatory, they fall victim to the same problems as “badges.”

There are plenty of things that are done by the school to make student privacy completely impossible. This mainly centers on Chromebooks.

For example, on school Chromebooks, the geolocation permission is enabled for all sites, with accuracy 10–15 meters. This is dangerous! While your location within the school is not exactly classified, it can also show the exact position of students’ homes to a malicious or ad-infested site. (Please do not dismiss the severity of this statement.) I also want to note that our district has completely blocked installing any extensions like uBlock Origin, which block ads and trackers, and also include a few other privacy-enhancing features.

Aside from the broad claims and shorter analyses of specific companies, there are some characters that should be seen closer.

The reason you clicked this article.

e-hallpass, now called Securly Pass, is an app that keeps track of students’ movement throughout a school.4 It has features to restrict capacity of destinations (generally bathrooms) and prevent different pairs of people from being in the hall at the same time. e-hallpass was the first program sold that performs this function, but many competitors have cropped up with similar functionality; for example, SmartPass and Minga’s Digital Hall Pass. It’s all the same.

In recent history, in November 2022, Securly Inc. announced their acquisition of Eduspire Solutions, the original developer of e-hallpass. Securly’s flagship product was for years a system similar to GoGuardian, allowing teachers and administrators to monitor and control student devices. In recent years, the company has branched out to provide a whole suite of products. e-hallpass now goes by Securly Pass, but many students continue to use the old name.

Criticism of e-hallpass has been widespread. Motherboard described e-hallpass as “a tool that monitors how long kids are in the bathroom” and cited “over a dozen” online petitions calling it “creepy.” At Gateway and many other schools, students are all but unanimous that “I hate e-hallpass.” (This statement was repeated verbatim at least a score times.)

10th grader Kira Glass said, “There could be literally no one in the bathroom and it will say, oh, maximum capacity! I feel teachers forget about it and just let it run forever, and then you get blamed for it. You could get a detention for being supposedly out of area when you’re actually in a classroom.”

“It’s so annoying when I need to go to the bathroom and it [the app] says it’s maximum capacity. Half the people are talking to Mrs. Kimmy when I need to use the bathroom,” 9th grader Ariana Bradley said. Many people commented on the capacity restriction for the bathroom.

“There should not be blocks,” 9th grader Chloe Lopez commented, adding that the administration should “just let people fight it out.”

10th grader Davidson Dunn expressed extreme distaste for e-hallpass, in a manner that The Chomp has opted not to publish. Additionally, Dunn said: “e-hallpass is very unprofessional because it’s prohibiting students from learning by stopping the lesson, and preventing the teachers from doing their job by forcing them to make the pass.”

Teachers also find e-hallpass frustrating.

“I find it really difficult to manage it on a daily basis,” said Ms. Harvey. “It’s really daunting to use when there are pass blocks and you have to keep checking the system to allow students to use the bathroom.”

Mr. Widener agreed. “e-hallpass is great in theory, but occasionally in practice becomes very cluttered to manage.”

“They started it because they wanted to stop using the paper passes,” Anastasia Sims, a senior at Gateway, told The Chomp. “I don’t think there was any particular turning point, but things may have gotten a bit crazy. They started using it electronically and they started using it during eighth grade, and then COVID hit; we came back full-fledged e-hallpass.”

Other schools have shared that position. Rolla High School in Missouri dropped the program for the 2022–2023 year; one teacher told their student publication ECHO that “[it was] a logistical nightmare for administrators.” They found that while it can help with some problems, it causes more trouble than it’s worth.

At Gateway, it is argued that it, while annoying, is a necessary evil. 10th grader Lucas DiCicco said, “Although its quality can be questionable at times, we have more than enough reason to make use of it. If the students could be trusted to act responsibly on their own, there wouldn’t be a need to have it in the first place.” Ty Brashear made similar comments for The Knight Times. (The Knight Times is the student newspaper at Kings High School in Kings Mill, Ohio.)

Rachel Lantz is the attendance secretary for Kings High. “I think e-hallpass is a good way to track students and know where they are in the building,” Lantz told The Knight Times. “It is also useful to look back on e-hallpass history, if need be, and check to see the frequency and timing of consistent uses.”

To that end, Davidson said, “With e-hallpass, people still go to the bathroom and sit there for longer than they should be; it doesn’t solve the problem of kids going into the bathroom and wasting their time.”

But even considering the argued practical side, many teachers are more swayed by its downsides. Several teachers, when asked about its positive qualities, couldn’t list any. Ms. Danza’s final comment to that end was that “the more you use it, the better you get at using it.”

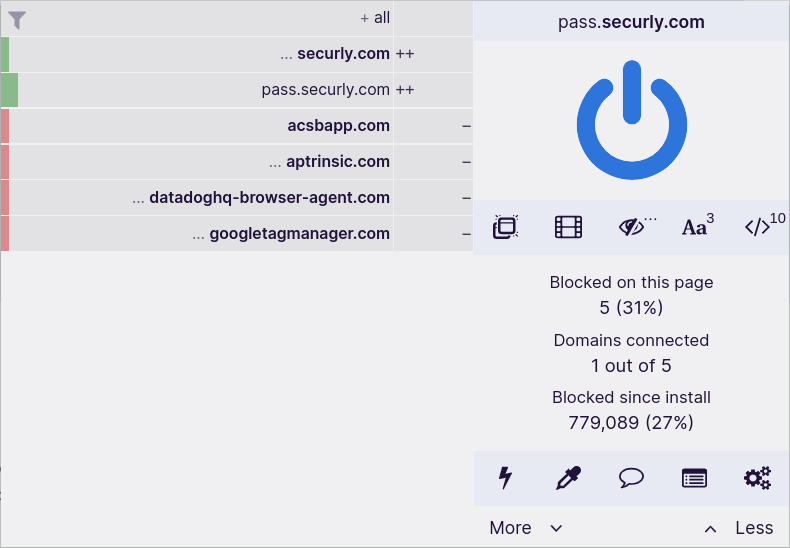

As for privacy considerations, there were 3 trackers blocked on just the login page for Securly Pass:

(Aptrinsic and Datadog provide analytics data for application developers, which while useful for developers, is likely outside the scope of educational consent under FERPA. Google Analytics can do the same, but is used by Google for tracking purposes as well. It’s generally considered deprecated by privacy professionals, especially since its ban in much of the EU. This is also very questionable under FERPA’s educational consent exception.)

e-hallpass has proven to be an extremely controversial tool, with administrators arguing its disciplinary utility and teachers and students struggling with the practical matter of actually using it. This is a battle that cannot end without intervention.

The eternal boogeyman of teachers trying to unblock websites.

I was originally inspired to write this part a few years ago when GoGuardian introduced their always-active popup injected into pages, which states that teachers and administrators can see your activity “to keep you secure and scholarly.” The main problem with this claim, critics say, is that students need to learn how to manage their own time. Having everything already decided by blocking anything deemed inappropriate or distracting does not instill time management skills. And GoGuardian objectively does nothing to keep students secure, and may indeed do the opposite.

GoGuardian, of course, is that persistent monitoring system (read: spyware) employed by Gateway and countless other school districts to restrict your access to certain online resources, and of course secondarily to make sure you’re not playing a game on some other tab (as if that’s their main prerogative in education). Most problematic is its use to censor a large tranche of online material on questionable bases. But student privacy is a significant concern as well, given it (and the Google Chrome browser) send literally all activity to the school for potential review.

Similar software is also sold by Securly, Blocksy, and Gaggle.

Concerns about the efficacy of content filtering have been widespread since its introduction. Website blocklists commonly used by schools are known to be unreliable; at Gateway, a combination of filters from GoGuardian and Fortinet’s garbage network firewall5 block websites including: Teen Vogue, Rolling Stone, Planned Parenthood, Amnesty International, Mashable, xkcd, and TradingView. Math is Fun, apparently.

In addition, my colleague Desmond McCue remarked, in an entirely overamused voice, “They blocked Human Rights Watch!!!”

An article in The Pitch, the student newspaper at Archie Williams High School in Northern California, started by citing the Children’s Internet Protection Act for its role in promoting web filtering in schools. The law requires schools to block “visual depictions that are obscene, child pornography, or harmful to minors.”

Their district’s Senior Director of Information Technology, Rose Chavira, told The Pitch: “The categories that get blocked for students typically are adult materials [such as] nudity, anything risky, and gambling. Anything that would be considered a security threat, like malware or viruses [is also blocked].”

But none of those would explain the websites blocked at Gateway. As a recent investigation by The Markup further reported, many schools go far beyond blocking adult content. Among those topics, suicide prevention websites, abortion and advocacy organizations shine through. While Gateway is not among schools that block suicide prevention websites, our filters don’t stray away from the latter categories.

Matt Barker, one person from Gateway’s technology department, has not responded to a request for an interview or written questions. But the explanation for why these are blocked isn’t local. While GoGuardian doesn’t determine what websites are blocked at a school, they do provide predefined filter categories. Securly and Fortinet, along with myriad other filtering or firewall softwares, do the same.

Outside of blocking specific websites, GoGuardian uses keywords on the page to flag content. Now an archaic example, simple substring filtering has long been known for its undesired consequences. This is called the “Scunthorpe problem,” where the website for the town of Scunthorpe, North Lincolnshire, England was blocked by various profanity filters for the second through fifth letters of its name. Dumb filtering and modification still happens on other platforms; for example, the iOS app for the social media app formerly known as Twitter, until very recently, changed “twitter.com” to “x.com”, leading to the humorous case of roblotwitter.com. And GoGuardian applies it to page content. There are obviously inherent limitations to GoGuardian’s approach of simply filtering by keyword.

That concern isn’t entirely theoretical. In my experience, a few years ago, a Latin numbers GimKit was flagged for the simple appearance of the word sex. According to records requests which were obtained by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, at the Alvord Independent School District in Texas, students have been flagged for legitimately educational websites like that of McGraw-Hill and MindMakers Coding, a picture of a woman wearing glasses, numerous online games, and web searches including “what are all the reasons to slay” and “how did marilyn monroe die.” Their own reporting mentioned that the keyword unblocked made up a significant portion of “explicit” flags; “attempts to access pornography are actually relatively rare.” To that end, EFF hosts the “Red Flag Machine” quiz, which asks you to identify which words were flagged on a set of websites.

But more importantly, EFF found, filters can disproportionately target LGBTQ+ content6 and content involving people of color. While LGBTQ+ content is no longer flagged by the software per se, it inherently incorporates words such as sexual (as in orientation, perhaps) and words describing anatomy. It doesn’t discriminate between an educational use of the word Nazi, its derogatory use by left-leaning writers, and use actually promoting neo-Nazi movements. And GoGuardian also disproportionately flags Black artists’ music.

Reviewing GoGuardian’s blocks, one learns two things: almost anything can be used as a sexual metaphor, and if any given word has appeared in Penthouse more than once, it will be flagged.

One may be able to justify any of the earlier listed blocked sites, however, with some combination of points that students must “keep their minds on their own schoolwork” and not “broadcast political or any other views to educate and inform the public.” But it remains that a significant number of educational or completely inoffensive sites have been blocked. Architect Magazine. Target. Verso Books. Mrs. Gehring commented, “I was shocked that that website [a geometry demonstration] was not blocked the other day.”

Other reporting on GoGuardian has not focused on filtering, instead on privacy. The Pitch’s headline indeed distinguishes between protection and privacy.

Prior to 2015, GoGuardian was able to remotely activate students’ cameras; in 2010, the Lower Merion School District, near Philadelphia, settled for $610,000 in federal court for using this feature of another software. But the privacy concerns from those incidents continued through 2018, when one junior spoke at a school board meeting, saying, “We have students so concerned about their privacy that they’re resorting to covering their [laptop] cameras and microphones with tape,” Motherboard reported.

Apart from that, GoGuardian is able to monitor students’ screens and, per the previous source, used to have keylogging capabilities. That means that anything a student types into a Chromebook could be used against them. It also keeps track of every site that students visit, just as the underlying Chrome browser does, and syncs it to the cloud.

But post-Roe, surveillance tools can be used to track students receiving abortions or gender-affirming care. Because they may send alerts to school resource officers (also known as “police”) and false flags are so common, searches related to abortion can fall into the hands of prosecutors quickly. Additionally, The Markup says, schools can simply add abortion-related keywords to the flags. They cite a few instances of browsing history and messages being used as evidence in abortion-related cases.

Four student journalists for The Budget in Lawrence High School of Lawrence, Kansas highlighted that the similar suite Gaggle has a chilling effect on journalism. GoGuardian Beacon, Securly Aware (formerly Securly 24), and Gaggle’s “student safety monitoring” suite all scan students’ emails, Google Docs, and personal social media to detect threats. Their prior reporting included student art being very regularly flagged as pornography by the software.

“As student journalists, much of the work we do surrounds mental health,” they write. Student privacy and free speech violated in the name of mental health. They went as far as to say that the phrase “You’ve been Gaggled” has become commonplace to describe censorship. For them, the software has become an effective gag order barring any reporting on potentially flagged subjects.

Teachers say it helps students stay focused. Sophie Dreskin, in support of GoGuardian for the Berkeley High Jacket, said that teachers can use the chat feature as a gentle push to keep students on task; and alternately, teachers can simply close tabs on students’ computers. In a now-deleted story, The Gator Gazette, the student newspaper for Wellington Landings Middle School in Florida (they did not respond to an email concerning this), said that in one student’s opinion, “This new app is just a way teachers can make sure you’re on task and not on some other site playing games.”

Others argue it’s not the school’s job. Amelie Jenks, a senior at Archie Williams, told The Pitch: “I believe part of the responsibility of being a student in high school is rising to expectations and being trusted with things like computer use. Preparing for college and more adult-level classes requires students to keep themselves in check without constantly having to be supervised by a teacher. If these sorts of standards are expected for students to be able to regulate their own online access during class, it is more likely that students will meet those standards by themselves.”

“I don’t think [teachers] should block students from using computers because a student has their own right to use a computer and it’s not the teacher’s responsibility to control what I can see,” Quilla Ross, a freshman at Archie Williams, said. “Especially in high school.”

One parent told Wired, “Obviously, the internet is a big distraction, and we’re working with them on being able to manage distractions. You can’t do that if everything is already decided for you.”

For GoGuardian and student monitoring as a whole, student opinions remain split. At Gateway, a few students brought up how ugly the “blocked website” screen is, but most were ambivalent to its use. Teachers generally agreed that it can be annoying when useful websites are blocked, but didn’t argue with the technology itself. Other schools are more interesting.

In the Berkeley High Jacket’s piece, on the pro side, the usual arguments cropped up. But Penelope Purchase, a journalist for the Jacket, took a different approach, arguing that the specific tool GoGuardian is unnecessary. “All WiFi routers have apps capable of blocking websites directly through WiFi. With resources like these, AI systems, game websites, and social media could be blocked without invading students’ privacy.”

A different Pitch at Walter Johnson High School in North Bethesda, Maryland reported that for 2024–2025, Montgomery County Public Schools would be dropping the program due to low usage.

The district’s Chief of Strategic Initiatives, Stephanie Sheron, told the Walter Johnson Pitch, “We have about fifteen thousand teachers [in MCPS]. In this school year alone, [only] six thousand teachers use [sic] GoGuardian at least once.” The article mentions that GoGuardian costs about $230,000 to be implemented there, the article says; one student said that “the money is going to waste.”

At Gateway, the program costs around $12,000, according to a records request.

In any event, with all of its petitions related to school filters, it’s very telling that Change.org is caught in the blocking crossfire.

Edtech is a thriving industry, but it is inherently coupled with abuses of student data and other corporate practices to harm schools.

Software as a service is not a desirable alternative, and has been called “service as a software substitute” because it imposes even more stringent licensing requirements than most proprietary software.↩︎

I include a link to a Microsoft breach because it includes employee data being compromised; teachers shouldn’t be apathetic to the plight of the students.↩︎

Their site tracks users without explicit consent beforehand, which violates GDPR, and does not provide a clearly visible opt-out mechanism, which violates California and Colorado law. Despite being “Non-Personal Information” according to their privacy policy, in reality, it is likely still linked to your identity; otherwise, it is extremely easy to reidentify advertising data. They claim “We do not disclose any personal information to third parties for marketing purposes” but their partners “use [it] for online behavioral advertising.” Why trust a company which literally violates those laws to certify compliance with them?↩︎

An app which tracks when, how frequently, and how long students use the bathroom—data for (ab)use by teachers and administrators—and stores that on a private company’s server with few guarantees towards privacy or security. Charging over $3,000 per year for a small school when, realistically, the app could run on one mid-level VPS and managed database (let’s say $30/month). Fascinating.↩︎

Fortinet has had several high-severity (in fact, critical) vulnerabilities just this year. Specifically: CVE-2024-21762, CVE-2024-23108, CVE-2024-23109, CVE-2024-23113. Last year, a SQL injection vulnerability. In 2023.↩︎

In some states, anti-LGBTQ+ filter logs may be weaponized against transgender students per laws requiring disclosure to parents.↩︎